Like most of you probably already know, 2022 was a terrible year for asset markets. Stocks were down, bonds were down, etc. The silver lining in all of this is that interest rates went up quite a bit. Bonds that were effectively paying 0% two years ago are now yielding north of 5.5%. Just this week, 10-year treasury yields hit 5%, levels not seen since July 2007. To contrast, in the depths of the pandemic the yield on the 10-year bond reached a low of 0.51%.

A couple of days ago we were talking with a client about possibly locking in these rates for the long term. In theory if you’re happy with a ~5% return you could create a treasury ladder and be done with it. Assuming the US doesn’t default, you are guaranteed a 5% rate of return (and if the US defaults, there are bigger issues going on in the world than your investment portfolio). So why not just throw all your money into 30-year bonds yielding 5% and call it day? There are several considerations you have to keep in mind and the most important one is mark to market risk. As a reminder, the 20+ year bond ETF (TLT) is down 15% this year and is down 48% since it’s all time high in June 2020. 30-year rates went from 1.9% to 5% over that time, and as you know, as rates go up, bond prices go down.

Given the way bonds work, if rates go up to 9.5% (same percentage point move), TLT wouldn’t be down another 45% (because of bond convexity and higher level of starting yields), but it would definitely be down quite a bit. So even though you can guarantee (assuming the US doesn’t default) a fixed return of 5% today, you can still be down quite a bit from here. So, do you really have a 30-year investment horizon? Thirty years is a long time, (almost my entire life!) think of the last asset you held for 30 years, probably nothing, maybe only your house? What happens if you need the money for something else? You might be forced to sell at an inopportune time because of a situation outside of your control.

That 5% looks enticing today, given we’ve witnessed almost 15 years of sub 5% rates. The question is are 5% rates the exception or the rule. Should we expect rates to trend down to the post GFC average of 3.25%, stay at the 4.9% average from 2000 – 2007, or continue rising to the 6.9% average from 1989 – 1999? In all three cases your long-term return would be exactly the same, whatever yield you buy the bonds at. But the path to get there will be very different. Scenario one you’ll get some mark to market gains early on, in scenario two price will stay roughly flat, and in scenario three you will probably be in a pretty steep drawdown at the beginning. Obviously, all this depends on how fast rates move, but the point is that even though the return is close to being guaranteed the path to get there might be painful. If you are not 100% sure you will be able to hold the investment to maturity, then you run the risk of incurring a loss in an almost guaranteed investment.

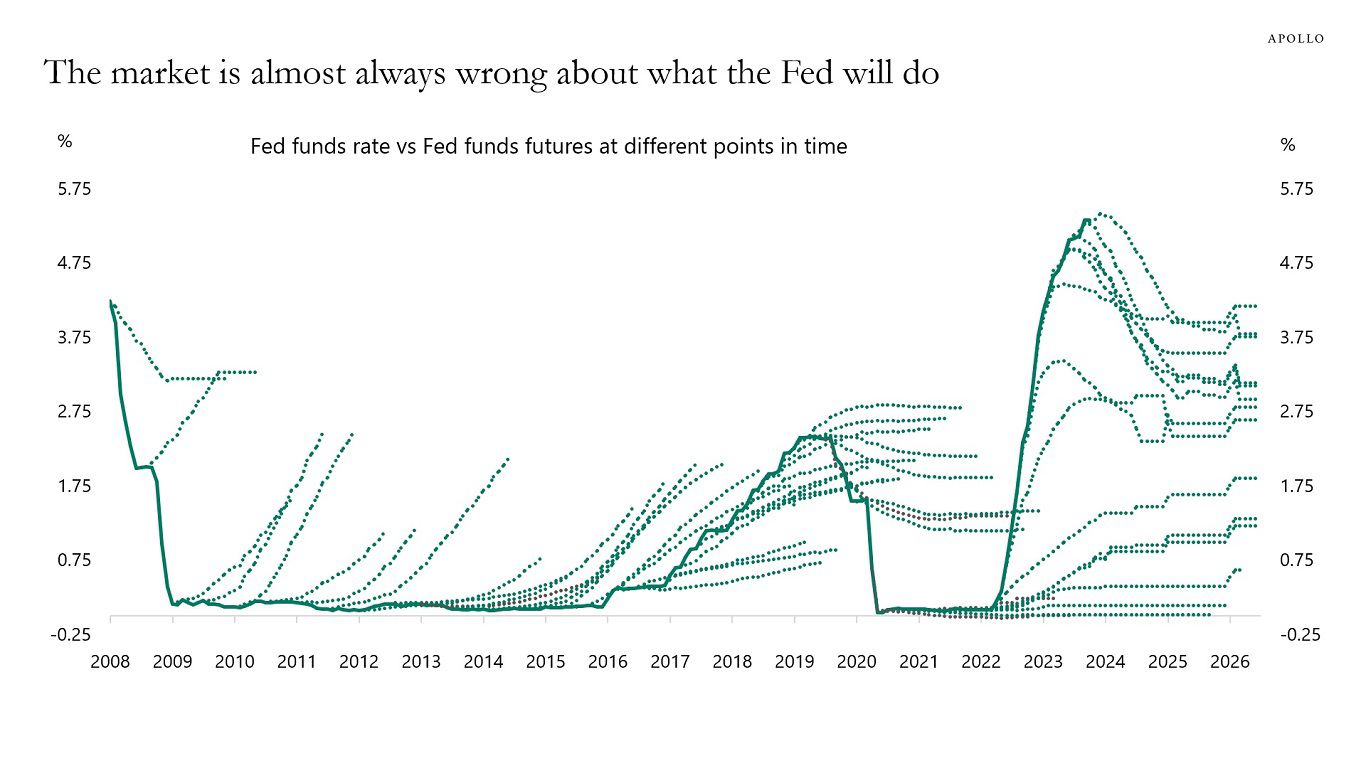

And if you’re think thinking you can predict the path of interest rates, please think again. The chart below shows market expectations of what the future fed funds rate will be vs. what it actually was (credit: Torsten Slok – Apollo).

The good news is that asset prices don’t live in a vacuum. In theory all asset prices should be related to one another (even though in the short term we might see large dislocations). Think of it this way, let’s say you are raising debt for a new business. Back when risk free interest rates were 0%, investors might be happy to get 5% for a risky investment. Now that risk free rates are at 5.5%, no one will lend you money to undertake a risky investment at the same 5.0% (why some still invest in Costa Rican banks’ certificates of deposit at lower rates than 3-month US treasuries is beyond us). Let’s say the spread stayed the same, then the investor would require a 10.5% rate in order to say yes. So, the return for the risky investment goes up from 5% to 10.5%.

The same concept applies to stocks and other investments (it’s easier to understand the bond example but the same concept applies elsewhere). In fact, this is why stocks tend to drop when interest rates go up sharply. In essence the price of a stock is a sum of all its future cash flows discounted back to today. When interest rates go up that discount rate also goes up. This has the effect of lowering the net present value of those cash flows and therefore the stock. Lower prices, all else equal, will lead to higher returns (also depends on what happens to the expectation of future cash flows, which may be correlated to the increase in rates, but we’ll leave that for another day). Therefore, higher interest rates should lead to higher returns across the board (at least in theory).

The painful part of higher interest rates is the transition from a low-rate regime to a high-rate regime. The way to get to higher expected returns is for prices to fall. So, if you were fully invested you did lose money. The benefit of higher rates of return will be for new money you put to work. So, if you have uninvested cash, you should be happy rates are going up and stocks are going down. And if you have a lot of cash, you should hope rates keep going up.

BREIT’s True Value May be Closer to 60% of NAV

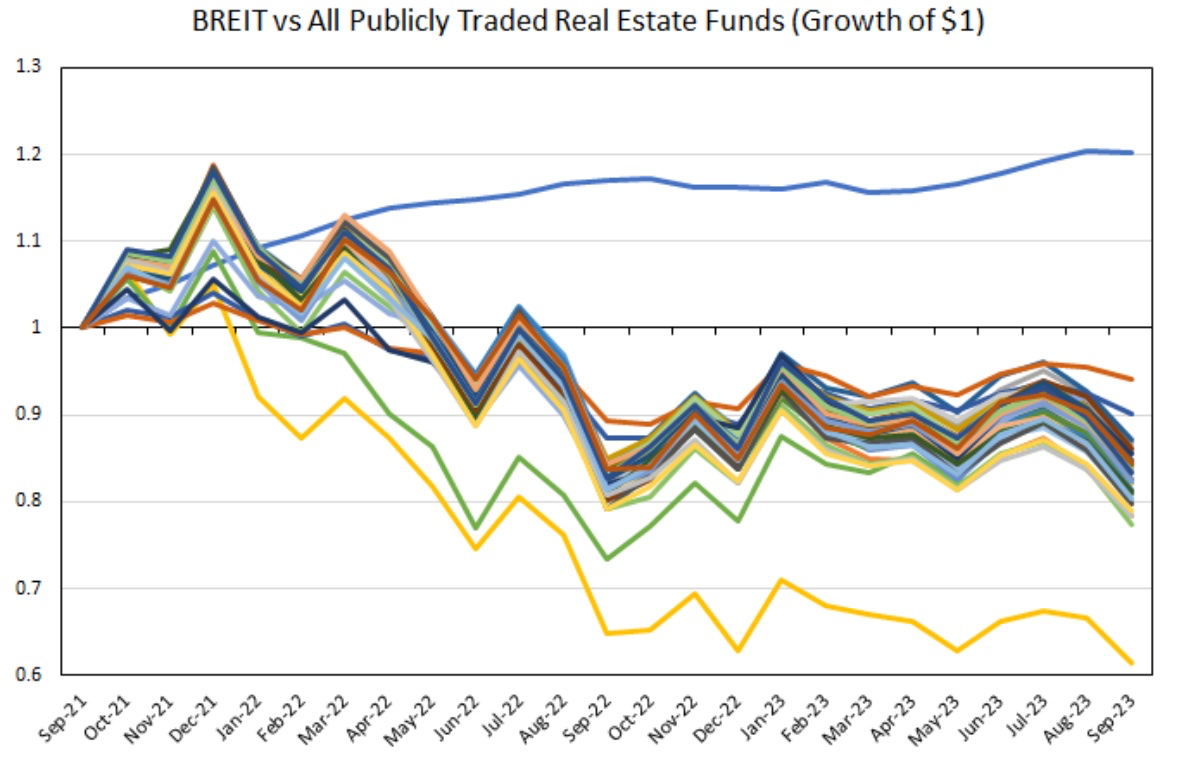

We were pretty early to criticize BREIT last year (we used the same GIF but it’s just so good we had to use it again). As a quick refresher, just north of a year ago, we sat in on an investment committee meeting for a foundation, and the bank pitched BREIT as a great diversifying alternative since it was up in a year where pretty much every other public REIT was down. Key word here is public. Our criticism was that BREIT was essentially making up their marks (making up is a strong word, probably should be strongly influencing, but you get the point). This chart summarizes our point (credit to Jake (@EconomPic).

Is one of the largest (the largest?) REIT in existence that good at delivering alpha (generally size is the enemy of performance)? Or is it the fact that it’s private vs. all the others which are public? Anyways you know the answer (hint: private funds can “influence” their valuations). If you want more details, please read our previous commentary (written over a year ago) or reach out. We were early enough to call this before they started gating redemptions.

Well now there are tender offers to buy BREIT shares at $9.27 per share, which is a 38% discount to the September net asset value (NAV) of $14.88. Mackenzie Capital Management is offering to buy the shares from their clients at this price in order to provide them liquidity. Is the true NAV really $9.27? Probably not, Mackenzie should get paid for being a liquidity provider. But 38% discount seems steep for just providing liquidity. The true NAV is probably somewhere in between. Based on the graph above we would probably guess it’s between $9.92 – 11.16. However, like we always say in the end the price of something is what someone is willing to pay. BREIT itself will pay $14.88 but only to around 2% of the fund a month and 5% a quarter. Mackenzie will pay $9.27.

If you truly believe BREIT is providing amazing alpha, then stick with it by all means. If you believe it’s a fiction of private valuations, then the trade here would be to sell BREIT (good luck trying to get your money out) and buy one of these public REITs that best resembles BREITs portfolio (not investment advice!).